Bill Knight column for Mon., Tues. or Wed., Dec. 8, 9 or 10

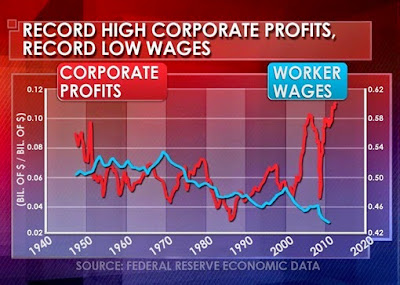

Wage stagnation stems from businesses abandoning their historic role of operating for social good as well as commercial gain, according to several recent analyses.

Third-quarter corporate earnings were about 10 percent – the widest margins in 22 years, according to the Wall Street Journal’s Justin Lahart. He wrote, “A big reason margins have continued to widen is wage gains – or more aptly, a lack of them. Average hourly earnings continued to grow weakly in October, and were up just 2 percent from their year-earlier level, according to the Labor Department. That is even though companies have been hiring over the past year at a faster clip than economists expected, with the unemployment rate falling to 5.8 percent last month from 7.2 percent a year earlier.”

The New York Times reported, “Since the recovery began in mid-2009, inflation-adjusted figures show that the economy has grown by 12 percent; corporate profits, by 46 percent; and the broad stock market, by 92 percent. Median household income has contracted by 3 percent.”

Further, as the Washington Post’s Chico Harlan reported, “Since 2006, the number of Americans seeking full-time work but reluctantly holding part-time jobs has risen 65 percent, to 6.8 million.”

The disconnect is worse when considering that business no longer even pays for good production.

“Despite increasing economy-wide productivity, wages for the vast majority of American workers have either stagnated or declined since 1979,” according to “Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge,” a recent Economic Policy Institute report. “Between 1979 and 2013, productivity grew 64.9 percent, while hourly compensation of production and nonsupervisory workers – who comprise 80 percent of the private-sector workforce – grew just 8.2 percent.”

The lost link between work and wages comes down to business gaining power over both workers and elected officials, and exerting that influence to maximize profits at the expense of employees and society.

Business had a choice and made one damaging to their labor forces and the country.

“A century ago, industrial magnates played a central role in the Progressive movement, working with unions, supporting workmen’s compensation laws and laws against child labor, and often pushing for more government regulation,” wrote James Surowiecki in The New Yorker magazine. “This wasn’t altruism. The reforms were intended to co-opt public pressure and avert more radical measures.”

After World War II and through the Johnson administration’s Great Society programs, many businesses cooperated with reform efforts, he continued.

“Corporate leaders formed an organization called the Committee for Economic Development, which played a central role in the forging of postwar consensus politics, accepting strong unions, bigger government, and the rise of the welfare state,” Surowiecki said.

Today, there are no such “centrist” business organizations with political clout left, he added.

Adding insult to injury, 35 percent of investment capital put up by limited partners comes from pension funds, according to “Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street,” by Rosemary Batt and Eileen Appelbaum. That means, Robert Kuttner wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Workers’ own funds become part of the financial system that drives down workers’ wages.”

Another consequence of the lack of wage growth is its contributing to rising household debt, a factor in the Great Recession of 2007-2009, says Jonathan Tasini, a union activist who blogs at Workinglife.org.

“The basic bargain was roughly this,” he says. “If you worked hard and became more productive, you would see that sweat of the brow in your wages. And from the post-war era until the 1970s, that deal basically held. If [that] had continued, the minimum wage would be more than $19 an hour. The minimum wage!

“In short: people had no money coming in in their paychecks so they were forced to pay for their lives through credit – either plastic or drawing down equity from their homes,” he continued.

Lahart, in the Wall Street Journal, added, “Eventually, things will change. Companies will no longer be able to keep labor costs at bay, interest rates and inflation will rise, and investors’ focus will swing back toward growth. But as the persistence of wide profit margins has shown, eventually can be a long time coming.”

[PICTURED: Chart from independentreport.blogspot.com.]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.