Bill Knight column for Thurs., Fri., or Sat., Aug. 13, 14 or 15

Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner wants Illinois to let municipalities go bankrupt, and State Rep. Ron Sandack (R-Oak Grove) has introduced such a measure in the legislature. But neither has spoken about the financial consequences to people who own municipal bonds if Illinois communities go bankrupt like Detroit, Stockton, Calif., Harrisburg, Pa., or Jefferson County, Ala.

Bondholders who lent money to municipalities would be hurt, as well as the insurers who guaranteed those bonds, and many of those bonds are owned by regular people, directly or indirectly.

This month, Puerto Rico’s default shows that such actions could be a much bigger problem for investors than Greece’s meltdown. Everyday Americans own Puerto Rico bonds, and 20 percent of bond mutual funds own some Puerto Rico bonds, according to Morningstar. Puerto Rico Gov. Alejandro Garcia Padilla has asked Congress for permission to go bankrupt. (Interestingly, Puerto Rico last month made all its scheduled debt payments EXCEPT its Public Finance Corporation obligations, possibly because those are mostly owned by credit unions and other ordinary people, not Big Banks with armies of lawyers to fight back.)

Such government or municipal bonds are usually tax-exempt, and some are attractive, if risky. For instance, Chicago issued $347 million in tax-exempt bonds in July that yield up to 5.69 percent returns. And a T. Rowe Price tax-free muni fund, according to a U.S. News analysis, “has returned 5.11 percent over the past year, 5.05 percent over the past three years, 6.53 percent over the past five years, and 4.82 percent over the past decade.”

Bonds are sold because they’re backed up by government funds – or the power to raise money. That would change dramatically under the bill from Sandack – a former Oak Grove mayor, incidentally.

Fortunately, it faces a fight.

Municipal Market Analytics partner Matt Fabian told The Bond Buyer, “In Illinois, it’s unlikely that a bankruptcy law would be passed, and even more unlikely that what might be passed would protect bondholders over employees. The cost of capital would very likely rise.”

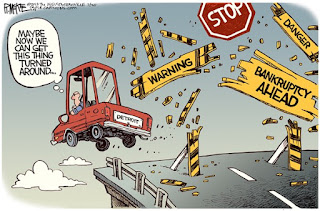

Still, Rauner’s “turnaround agenda” – which also proposes cutting state revenues to municipalities by half – contains his “Taxpayer Empowerment and Government Reform Package” proposing to “extend to municipalities bankruptcy protections,” an idea the Illinois Municipal League has pushed.

Of course, bankruptcies can modify or erase long-term debt, such as promised pensions or bonds, but the maneuver can be more treacherous than four-time bankrupt billionaire Donald Trump makes it sounds.

Federal bankruptcy law has many chapters. The most familiar are Chapter 7, which wipes out most debt; Chapter 11, which lets usually large companies reorganize finances; and Chapter 13, which protects the indebted party while repayments are planned. Chapter 9 lets municipalities go bankrupt – if their states permit it. Twelve states authorize Chapter 9 bankruptcies for municipalities; 12 more allow it under some circumstances, and 26 prohibit it. Since 2010, 37 local governments have gone bankrupt, just 8 municipalities, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. In the last 60 years, only 63 municipalities have filed for bankruptcy.

Even when possible, insolvent municipalities are supposed to provide evidence of their financial plight AND show they have no other options – like raising additional revenues to pay their obligations. (However, judges can’t compel municipalities to raise taxes or cut spending.)

Illinois already has a way to help – offering assistance through 1990’s Financially Distressed City Act, which was used to aid East St. Louis in 2013.

Is Rauner thinking Detroit is a good model for, say, Rockford? Chicago? In Detroit – despite Michigan’s constitution protecting pensions – a federal judge overrode that pledge, and pensions there weren’t even the main problem. Detroit was hurt far worse by the Great Recession and by the state legislature severely cutting funding.

“At a time when other cities were starting to recover [from the 2008 financial crisis], Detroit’s revenue was cut sharply by the state,” said Carrie Sloan of the Roosevelt Institute’s ReFund America Project. “That was what pushed the city over the edge.”

Does Rauner really want to push cities over the edge – and take investors with them?

In Detroit, which initially proposed paying 10 percent of what it owed, “creditors really took it on the chin,” commented bankruptcy lawyer Lee Bogdanoff, who assisted with Jefferson County’s bankruptcy.

San Bernadino offered to pay a penny on the dollar.

Some turnaround.

[PICTURED: Editorial cartoon by Rick McKee from the Augusta Chronicle via carbonated.tv.]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.